Should the PATHWAYS trial go ahead?

(The author has worked for a drug regulator and ethics committees that approve clinical trials.)

PATHWAYS is a randomised controlled trial of puberty blockers in children with gender incongruence. The announcement of ethics approval incited commentary in mainstream and new media that misunderstands the clinical context and motivation for the trial and fails to recognise its real flaws, including why the trial will ultimately fail. Controversial research draws commentary from the uninitiated, including journalists, who lack good instincts which are developed through focused application.

The trial and media response

The PATHWAYS trial is a randomised, unblinded (open-label) study investigating the effect of puberty suppressing hormones (PSH) in children aged between 10 and 16 years and with gender incongruence persisting for a minimum of two years. Recruitment will commence early next year (Roxby & Holt, 2025) with the primary analysis taking place after two years follow-up and with results expected in four years. All participants will receive PSH: 226 previously unexposed children will be randomised to an immediate or delayed (one year) start to treatment; all will receive psychosocial support (Fox, 2025). (There will be an untreated, non-randomised group with statistical comparisons based on matching. Here we focus on the randomised groups.) A £10.7 million award from the National Institute for Health and Care Research provides funding for the research (NIHR, 2025). Participants will consent to long-term follow-up stretching for the duration of the funding (5.5 years).

In November, awareness of the trial spread after ethics and regulatory approval was announced (King’s College London, 2025). Blunt and misdirected criticism appeared in newspapers (McColm, 2025) and on social media (Farrow, 2025), in particular X, including from British MPs who wish to “halt” this trial of “experimental drugs” (Lowe, 2025). The Leader of the Conservative Party, Kemi Badenoch, joined the chorus of voices to stop the trial, posting: “No child is born in the wrong body” (Badenoch, 2025). Criticism tended to impose on the trial the language of gender ideology, pseudoscience and the harms to children. Some also pointed to Big Pharma chasing profits, although gender incongruence remains a rare condition (i.e., prevalence <0.05%) and use is off-label and thus exclusivity incentives for orphan drugs do not apply (companies may nevertheless attempt off-label promotion; O’Neil, 2021).

However, the trial had already hit headlines back in February 2025 when funding was confirmed, with more precise criticism and general coverage emanating from the journalists at that time (e.g. Fox, 2025, The Times, 2025, Searles, 2025). The main point was the absence of evidence supporting the use of puberty blockers in children with gender incongruence. As noted in a systematic review by Dr Hilary Cass in April 2024, in “2014 puberty blockers moved from a research-only protocol to being available in routine clinical practice”, with the Dr’s assessment 10 years later noting that the evidence in favour of PSH is weak and the risks are not well understood (Cass, 2024). Those sceptical of early treatment declared the case settled (Turner, 2024). However, Cass’ review notes that the randomised controlled trial (RCT) is the gold standard of evidence and there are no good RCTs, and Dr Cass is “really pleased” about the upcoming trial (Roxby & Holt, 2025). The closest study to an RCT was a prospective study of 44 children with no control group (Carmichael et al. 2021).

Prominence of the RCT explained

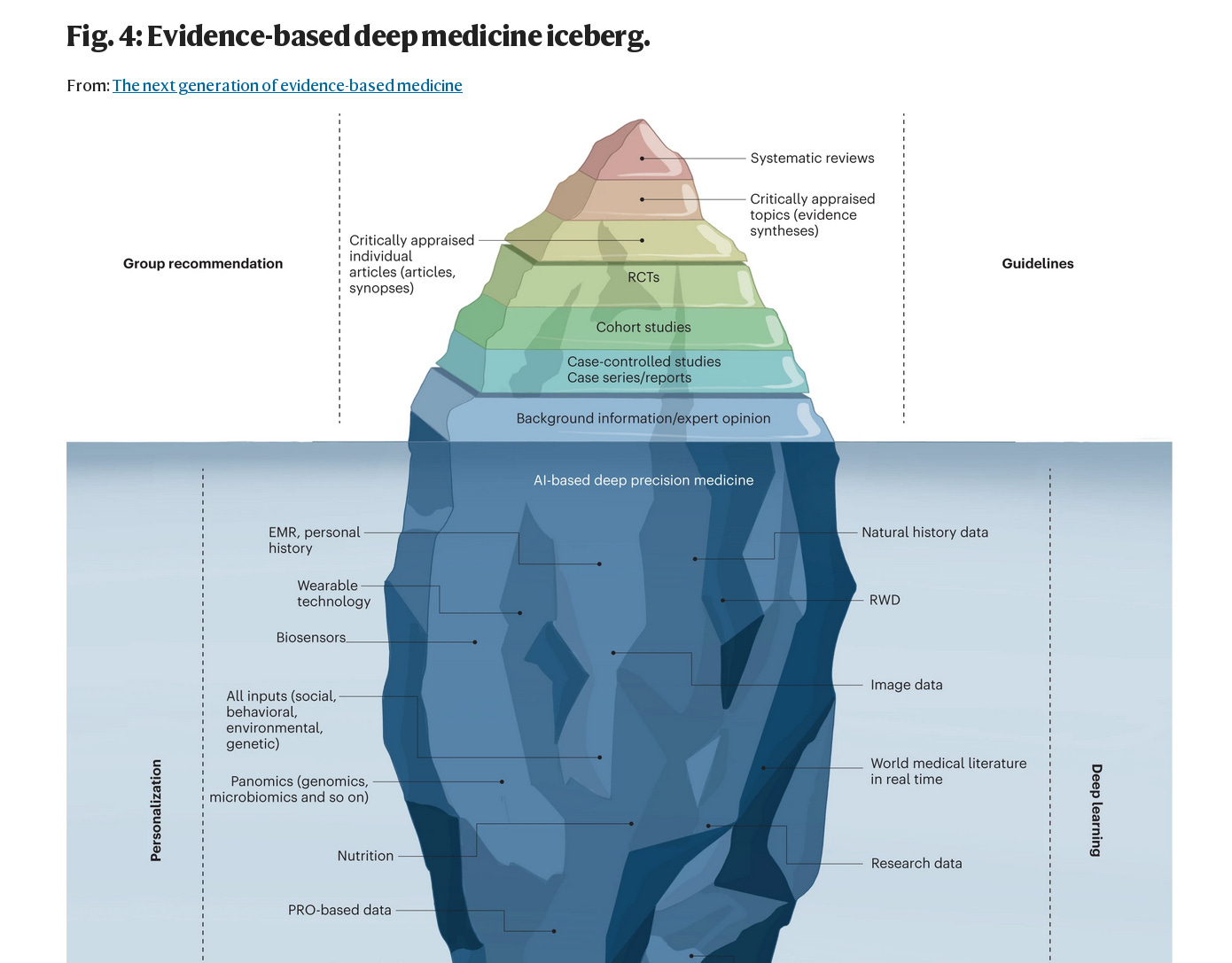

To understand this disconnect between the media and researchers (e.g., Cass) it is important to appreciate the impetus to construct a systematic review - they seek to evaluate the current state of evidence and are thus often over-emphasised and premature. I.e., there is an abundance of systematic reviews (the output of the evidence-based medicine proponents) and they should not be seen as a transmogrifier of meagre data into definitive conclusions, and a catchall analysis should not be relied on to establish efficacy. If the same systematic biases exist in each study dataset, combining them will only reinforce the biases, not cancel them out. Unfortunately, commentators often assume systematic reviews are the pinnacle of evidence, probably based on faulty logic: if the RCT is the gold standard and a systematic review collects the available RCTs, then the former transcends the latter.

A controversial systematic review would typically be seen as the justification for a trial. Consider the meta-analysis of magnesium in myocardial infarction (MI) which caused intense debate in the literature in the 90s (Teo & Yusuf et al., 1993). An association between MI rates and levels of magnesium in the water supply was observed (Woods, 1991). Trials of modest size were then reported for nearly 20 years before a meta-analysis of ten trials indicated that magnesium was efficacious (log odds ratio of mortality on magnesium relative to control was -0.49 with 95% confidence interval –0.27 to –0.73). This result reasserted the conclusions of an earlier informal review (Rasmussen et al. 1986). A large-scale randomised controlled trial (58,050 patients) followed two years later and found that magnesium was ineffective (log odds ratio 0.06 with 95% confidence interval 0.00 to 0.12). This study is referred to as ISIS-4 (ISIS-4 Collaborative Group, 1995). Or for an example in the other direction consider aspirin in MI where the evidence was weak and clinicians were not persuaded until a large RCT established the effect (ISIS-2, 1988).

This is why the lack of prior data is spelled out in the PATHWAYS trial protocol in terms of equipoise (PATHWAYS Trial, 2025) -- it provides the justification for an RCT. An RCT should be welcomed in the midst of such uncertainty and controversy because it has the ability to quash it like nothing else; it provides a straightforward analysis and thus cogent results that declare a single hypothesis the victor. However, to achieve such a clean result requires a concerted effort from a variety of experts and academia struggles to retain qualified people when competing directly with industry (Watson, 2023). The regulatory guidelines state, for example, that a trial must have a competent statistician (ICH-E9, 1998) and they are a scarce commodity. (We have written previously about how Pharma tried to solve this problem by funding statistics MSc’s but failed: Is Data Science a Scam?.)

It is worth noting that during COVID, with a high sense of urgency, the industry experts leaned on old-school methods -- the RCT -- to evaluate vaccines. Current talk of “data science” was put aside. This revealed that data science’s promise of “real-world data”, “advanced analytics” and “data insights” is mostly the marketing of software and degrees and there is very little that has seeped into regulatory statistics from this miscellaneous collection of tools. Generally speaking, you cannot have real-world data until the product is on the market and thus it cannot inform the approvals process; the black-box nature of machine learning is not palatable in clinical research or easy to validate; causal inference implemented via mediation analysis has not been widely accepted due its speculative nature, e.g., estimates showing wide confidence intervals and spurious conclusions (the proportion mediated exceeding 100%); and patient prediction, much like real world data, is hyped and remains the exclusive interest of academics and marketeers. The Data Scientists have suggested some adjustments that tinker at the edges for a gain in statistical efficiency (EMA CHMP, 2022), but this betrays their inexperience: the regulator will make you compare this model with the standard ANCOVA model and their own simulations show that the efficiency gain is lost compared with the standard baseline covariate adjustment. I.e., there is no gain. Also, when running a large RCT a small increase in efficiency is beside the point in comparison to the many other more relevant concerns. Frankly, a lot of the tools offered by the Data Scientists are just old ideas restored by an increase in computer power and a lack of inside information.

Hence the staid RCT remains unaffected by the evidence-based medicine experts and the Data Scientists who may opine that it is old hat (Schattner, 2024) and wish to supplant it in their hierarchy of evidence, or at least have some influence over it. The failed attempt to rebrand statistics as data science (which most people did not even detect) was fundamentally an attempt to open up statistics and thus open up the discussion.

Ethics and the need for clarity

Bearing all of this in mind, the claim by The Times (2025) in February that the “trial would turn children into guinea pigs” has it backwards. I.e., until the Cass review landed and the drugs were banned, children were treated as guinea pigs, and a randomised trial yielding a persuasive result would thus be needed to inform a standard of care. Currently, if many parents are doing their own reasearch, looking into treatment options, then a definitive but negative trial result could discourage access to PSH through unsafe means, and also alleviate the concerns of those who believe claims of suicide are used to manipulate parents into supporting early treatment.

The visceral response, even among the journalists, relates to the exposure of children to experimental drugs (e.g., McColm, 2025: “We know that experimenting on children is monstrous. We know it.”). At this moment, all over the world, children are entering clinical trials in rare conditions where there are limited treatment options. Sample sizes are small and data quality issues arise because the condition is rare: investigator sites are inexperienced and historical controls may be needed for comparison. Statistical methods on these data produce a range of plausible estimates of efficacy and it is possible the experimental drug is merely a placebo with a side-effect. I.e., evidence gathering is not always straightforward, especially in these circumstances.

In the case of puberty blockers, in the absence of a quality RCT, evidence is even more sloppy and ambivalent. At least it appears reasonable to say that rates of depression are higher within this cohort: transfeminine 49%; transmasculine 62% (Becerra-Culqui et al., 2018); likewise for suicide (Suarez et al. 2024). There is some evidence of an effect of puberty blockers or gender-affirming hormones on depression and suicidality (Tordoff et al. 2022) but this particular analysis is highly contested (DHHS, 2025). Alternatively, a paradoxical age-dependent risk of suicide from anti-depressants (SSRI’s) has been described leading the FDA to add a black box warning in 2004 indicating a higher risk of suicidal ideation in young people. Naturally, this has also been questioned (Friedman, 2014).

While surveying these results we must also reckon with a perverse bias seen in psychiatric disorders: based on small event rates we are inclined to speculate that a treatment incites depression as an adverse reaction (e.g. media coverage of accutaine in the mid-1990s), while promoting cynicism about treatments intended to alleviate depression (much of the commentary on SSRI’s, e.g. Angell’s book The Truth About the Drug Companies). For whatever reason, in certain conditions we tend to believe the evidence is strong when the effects are unwanted and weak when they are desired. Or maybe we believe that a null result is less likely to be affected by bias than a result away from the null?

For example, Jordan Peterson has stated that “[t]here is no such [evidence underlying pediatric gender medicine] and every physician and psychologist worthy of their designations knows it”. But then he emphasised in at least 3 separate posts in one month (1, 2, 3) a feeble analysis of uncontrolled data suggesting an increased risk of suicide after gender affirming surgery. (‘Feeble’ because propenstiy score matching, the method used, has been shown to increase “imbalance, inefficiency, model dependence, and bias” (King & Nielsen, 2019), although the authors of this research describe it as “well-documented regarding its properties for statistical inference”.) Likewise, in discussion of the PATHWAYS trial, those against the trial use prior data to point to the risk of side effects while noting prior data are too weak to suggest any benefit exists, e.g., Genspect, 2024). Thus there is a rebuke aimed at clinicians for a lack of evidence and a subsequent rebuke awaiting them when they attempt to gather evidence (via the RCT).

Any such cynicism is aided by the fact that safety is generally more difficult to establish. To make the point and preempt haphazard interpretation of adverse events, one can plot estimates of the risk ratio for each adverse event type and arrange them in ascending order, with the value 1 appearing somewhere in the middle of the sequence: if we want to consider those at one end as causative, e.g. eye disorders, then we must consider those at the other end as preventative, e.g. hair loss (no one will want to do that). It is possible to design a study around a net-benefit type composite that captures safety by incorporating, e.g., discontinuation due to adverse events (see Composite variable strategies in ICH E9(R1) addendum). However the PATHWAYS trial does not lend itself to this approach and the sample size calculation would become more uncertain: there is uncertainty around each endpoint and amalgamating endpoints compounds uncertainty (it would have to be based on simulations and require a highly skilled programmer).

Thus we are left with the hope that the PATHWAYS trial built around efficicay is senstive enough to yield a compelling result.

Brief review of the PATHWAYS trial

Given this background, equipoise etc., the most pertinent considerations for an ethics committee become study design, quality (site monitoring), the ability to meet recruitment targets, and the drop-out rate (Fogel, 2018). Quality and recruitment rates are common concerns with any trial run by the academics: academic clinicians can be indecisive with data analysis and lack resources and standards (e.g. they are unlikely to have a dedicated programming resource, the statistician then writes the code, but it takes at least two seasoned programmers to write and validate code).

Looking over the study protocol and the standard operating procedures at the King’s Health Partners Clinical Trials Office (KHP-CTO, n.d.), one is reassured quickly that these researchers are up-to-date and they know what they are doing. However, although the analysis plan remains to be drafted, based on the analyses specified in the protocol we can say the trial is not designed to deliver a compelling verdict and will very likely produce equivocal results that elicit yet more discussion and controversy.

The primary analysis is Bayesian (with uninformative priors) which implies no statistical penalty for “peeking” when running an interim analysis. Although no interim analysis is planned it may be prompted by the external monitoring committee. Under these circumstances a regulator would usually demand that the researchers evaluate the operating characteristics of the set-up, meaning they would have to run simulations a priori to evaluate the Type I and II error rates. (Despite recent claims from the FDA and new draft guidance, the regulator won’t go full Bayes -- this would open up the analysis. Consider The Times, already noted, who say based on current data “there is strong prima facie reason to think ... any supposed benefits [are] negligible”. Their priors would overwhelm the analysis. With uninformative priors Bayesian estimates can look a lot like the classical estimates, only the interpretation changes.)

Also, the estimate of the effect is assumed conservative (the “treatment policy” estimand) because it ignores, e.g., participant drop-out. But if paticipants in the delayed arm drop-out prior to expousre this seems relevant. Thus the primary estimand may be contradicted by sensitivity analyses that target a pure effect by imputing data after the participant discontinues. To make things worse, the effect estimate lacks cogency -- the difference between means of the composite score derived from the 10-point questionnaire -- and this will push emphasis onto statistical significance when the power has been depleted by the estimand strategy. They should instead consider a transformation model which can offer more power (Buri et al. 2020) and, most importantly, produce meaningful estimates of the effect that are easy to communicate (exceedance probabilities). Otherwise, an unclear result begets further exploratory analyses and additional publications, e.g. subgroup analyses which will be under-powered.

In other words, things look imprecise and open to second-guessing by commentators who can claim they would have done things differently. The academics are inclined to use non-conventional approaches such as Bayesian methods, and for the most part that is a good thing. Convention in industry is not always a result of regulatory guidelines being imposed on analyses but instead a desire for efficiency and simplicity that is so strong it can perpetuate bad methods for years (see last-observation-carried-forward). However, the downside of the more liberal mindset of the academics is that indecision produces something that appears cobbled together and vulnerable to re-interpretation, and this is regrettable when the trial is of high public interest: see the trial of ivermectin that appeared during COVID, boasting a Bayesian primary analysis with adjustments for multiple testing -- a strange juxtapostion of Bayesian leanings and strict adherence to frequentist concepts (PRINCIPLE Trial Collaborative Group, 2024).

Under the circumstances, then, we can say the analytical approach taken in PATHWAYS lacks prudence.

The media’s peripheral understanding

We are operating in an environemnt where even the journalists who are eager to report on medical research fail to understand the RCT and spread confusion. Regarding PATHWAYS, Barnes (2025) thinks: 1) The psychosocial support is a confounder (the protocol indicates that psychosocial screening is employed “to identify any unmet needs and escalate these to appropriate services.”). Barnes says: “It is unclear how this design will allow the research team to judge to what extent any observed benefits or harms are due to the medical intervention, as opposed to the other support being provided alongside”. 2) Allocation of treatment to participants is based on matching; e.g.: participants will be “paired with someone with a similar condition”. 3) When referring to the exclusion criteria for entry into the trial Barnes notes that the sample is not representative and will skew evaluation of the drug: “The study has several entry criteria, but who is excluded is perhaps equally important, and highlights some of the difficulties the trial faces. … [A] significant number of children who might potentially benefit [are] ruled out, potentially skewing fair evaluation of the drugs”. At moments in the piece it is strongly implied that the design is inherently flawed as a result.

However, these are quite common misunderstandings. 1) Clinical trials are comparative (we do not put confidence intervals on individual treatment group estimates) and standard care, in this case psychosocial support, cancels out when calculating the treatment difference, i.e. the randomisation takes care of it. Note that any placebo effect is considered part of the measurable effect of treatment due to the open-label design, including variable application of psychosocial support. 2) The PATHWAYS trial uses minimisation to allocate participants to treatments. This is a reasonable approach despite well-known criticism (Senn, 2008). Describing this dynamic allocation as “matching” is simply a misunderstanding of the method or an improper description of it that would elicit concern. Matching will be used for the non-randomised arm and tends to over-promise (already noted above). 3) This is a typical ‘outsider’ perspective of clinical trials. As already noted, trials are not representative, they are comparative. Barnes has not identified a bias (a term that relates to the treatment effect estimate) alluded to by the word “skew” which is not apt. Researchers often discuss rectruiting patients who are sensitive to treatment (“enrichment”) and you may have a run-in period to identify them; and it is typical to exlcude patients who are previously exposed. None of this is unusual and the treatment effect itself tends to be constant across subgroups (Harrell, 2019).

Barnes raises further suspicion when noting the researchers failed to answer questions, e.g.: after the two year follow-up, will “data collected from those [who continue on puberty blockers] be included in any formal analysis”. Of course they will be in the primary analysis, this is a requirement. But analysing on a subset at some point beyond this loses the randomisation and the p-value loses its interpretation. Thus it would be descriptive statistics at best.

Such misunderstandings emphasise that, although the RCT appears to be a simple, old-school tool, its precise motivation and justification is sufficiently rarefied for important books to be written about its analysis, leaving many issues unknown to the journalists. Although some journalists, almost to their credit, ignore the clinical and statistical context completely (e.g. The Times article noted above) while podcasters are already discussing the trial and producing bewildering non sequiturs, e.g. James Esses: “potentially unlimited numbers of children can sign up to this trial” (McCormack, 2025). Alongside the podcasters are the Substackers who revelled in the ivermectin RCTs during COVID: one person published nearly 30 articles on the TOGETHER trial of ivermectin in his Substack titled Do Your Own Research (Marinos, 2022), and others made accusations of fraud (Kory, 2022). This activity can be spurred on by some academics who insist on doing their own re-analysis of the data (Bryant et al. 2021).

Thus the discussion is pulled left and right by sideliners, and instead of placating them with a clean result, the PATHWAYS investigators are likely to generate a grey area in which they can manoeuvre.

Conclusion

The PATHWAYS trial should not have received ethics approval because it is unlikely to be successful and if the trial produces a negative result it will be easy to dismiss due to insufficient statistical power, quality issues and the estimand strategy. Trials have become complex and the cost of running an RCT provides strong motivation to reduce sample sizes by implementing interim analyses, meta-analysis or Bayes. But under the circumstances these analytic choices feel needlessly complicated and uncertain (e.g., the interim analysis is a mere possibility). Who knows how those who “do their own reasearch” will misinterpret such choices, or in fact how they will interpret the inevitable systematic review of the failed small-scale studies languishing in the medical journals. The need for academics to publish can lead to over-analysis of datasets and as we saw during COVID the data sleuths feed on ambiguity and their guesswork proliferates on social media.

I.e.: the PATHWAYS trial should not go ahead in its current form because it will only generate more fodder for the sideliners. The analysis plan could resolve some issues.

Give us your thoughts: